The History of Pearling in Bahrain - A Glimpse into an Ancient Legacy

by: BTM - Fri, 01 Nov 2024

For centuries, Bahrain was the epicentre of the world’s pearling industry, producing some of the most prized pearls ever discovered. From ancient times to the modern day, the story of pearling is woven into the fabric of Bahraini society, economy and culture. Edwin D’Souza traces the history of pearling in Bahrain, from its early beginnings and golden age to its eventual decline with the rise of cultured pearls and oil. Despite the industry’s end, Bahrain’s pearling legacy remains a cherished part of its identity.

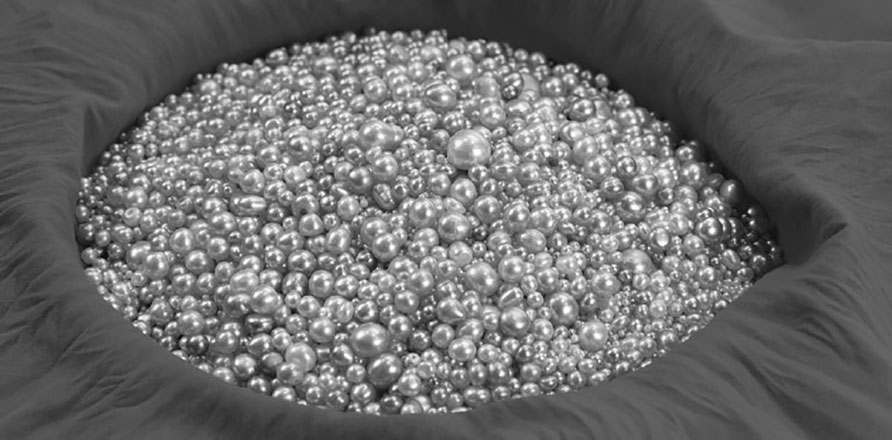

For centuries, the waters surrounding Bahrain were famed for producing some of the finest natural pearls in the world. The history of pearling in Bahrain is not only a testament to the country’s natural wealth but also an essential part of its cultural heritage, influencing its economy, society and even its global identity.

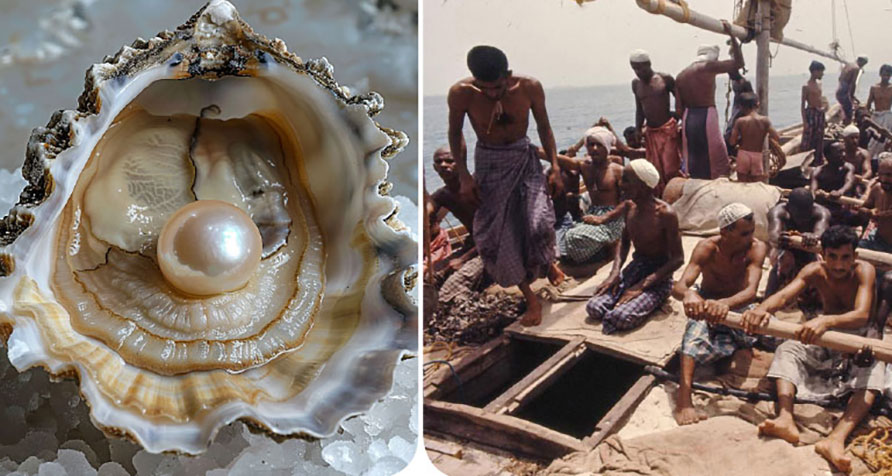

Pearling in Bahrain dates back thousands of years. Archaeological evidence suggests that pearl diving was practiced as early as 2000BC, making it one of the oldest known industries in the region. The abundance of oysters in the shallow waters of the Arabian Gulf made it an ideal location for pearling, and Bahrain’s geographic position helped it become a centre for this lucrative trade.

Historically, Bahrain’s pearls were highly priced for their purity, lustre and rarity. These natural treasures were sought after by royalty and elites across ancient civilisations, from Mesopotamia to the Indian subcontinent and the Mediterranean. The island’s name itself, Bahrain, is derived from the Arabic word bahr, meaning ‘sea,’ reflecting its intimate relationship with the surrounding waters and the pearling industry that flourished within them.

With the rise of Islam in the 7th century, Bahrain continued to thrive as a pearling centre. The region’s pearls were celebrated in Islamic culture, where pearls were not only symbols of wealth but also spiritual purity and divine beauty. Pearls are mentioned in the Quran, which further elevated their cultural significance.

By the 9th and 10th centuries, Bahrain’s pearling industry was fully integrated into the larger Arabian Gulf economy. Traders from Bahrain exported pearls to markets as far away as India, Persia, and Europe. The city of Basra in present-day Iraq became a major centre for pearling trade during this period, and Bahrain’s pearls were often exported through this vital trade hub.

Pearling remained an important part of Bahrain’s economy throughout the Islamic Golden Age, particularly under the rule of the Abbasid Caliphate, which saw flourishing trade across the Middle East and beyond. While Bahrain had other economic activities like agriculture and fishing, it was the pearls that formed the backbone of its wealth and international prestige.

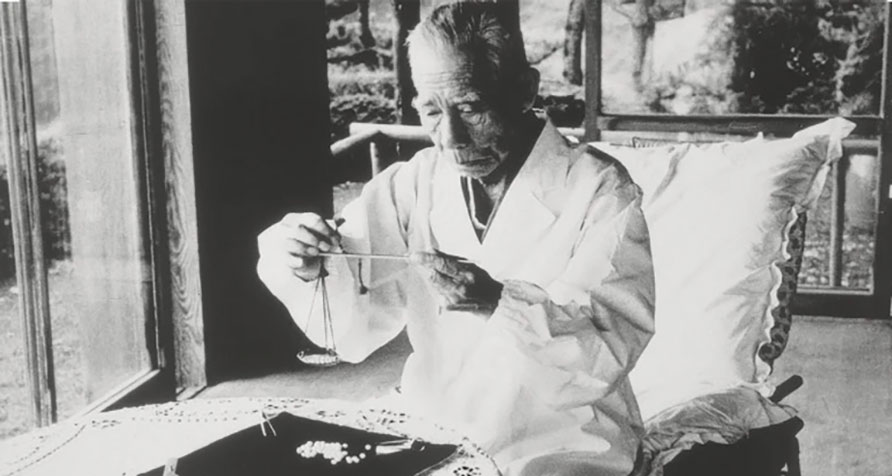

The pearling industry was organised into a structured, hierarchical system. At the top were the tawash, or pearl merchants, who financed expeditions and traded pearls. They were wealthy and influential members of society, often playing a key role in the local economy. The merchants would sell pearls both locally and internationally, acting as the link between the divers and the broader global market.

The divers, known as ghawwas, formed the backbone of the industry. Their work was perilous, physically demanding, and required immense skill. Equipped with minimal gear, including nose clips made from tortoiseshell and finger protectors, these divers would plunge into the depths of the sea, sometimes up to 30 metres, to retrieve oysters from the seabed. They faced numerous dangers, from drowning to encountering dangerous sea creatures, yet they were crucial to the success of the industry. Divers often came from lower socio-economic backgrounds, and despite their critical role, they earned modest wages compared to the merchants.

In addition to the divers, each pearling vessel, or sambuk, had a captain known as a nakhuda, as well as a crew that assisted with the ship’s operation. The nakhuda played an important role in managing the diving expeditions, navigating the seas and ensuring that the operations ran smoothly. Pearling trips, known as ghous, typically lasted for several months during the pearling season, from June to September, when the waters were calm, and weather conditions were favourable.

The 19th and early 20th centuries are often referred to as the Golden Age of Bahrain’s pearling industry. During this period, Bahrain was one of the world’s leading producers of natural pearls. The British, who had established a protectorate over Bahrain in the early 19th century, helped Bahrain gain access to new markets in Europe and India, further boosting the industry’s prominence.

Pearling was the dominant economic activity in Bahrain, employing a significant portion of the population. Entire towns and villages along the coast were sustained by the pearling industry, and the fortunes of many Bahraini families were built upon the trade. The wealth generated by pearling brought not only prosperity to Bahrain but also a rich cultural heritage, reflected in the art, music and traditions of the island.

In the early 20th century, European jewellers like Cartier and Van Cleef & Arpels became major clients of Bahraini pearls, recognising their exceptional quality. These global connections elevated Bahrain’s status as a pearl producer, and its pearls adorned the crowns and jewels of royalty across the world.

Despite its longstanding success, Bahrain’s pearling industry began to decline in the early 20th century, largely due to two major factors: the introduction of cultured pearls and the discovery of oil.

In the 1920s, Japanese entrepreneur Mikimoto Kōkichi perfected the technique of cultivating pearls in oyster farms, producing pearls that were more affordable and readily available than natural pearls. This revolutionised the global pearl market, leading to a sharp decline in demand for natural pearls. Bahrain’s pearling industry, which had thrived on the exclusivity and rarity of its natural pearls, could not compete with the mass production of cultured pearls from Japan.

At the same time, Bahrain discovered oil in 1932, which shifted the focus of the economy away from pearling. The oil industry quickly became the dominant source of revenue for the island, and many former pearl divers and traders transitioned into the oil sector. The discovery of oil brought modernisation and industrialisation to Bahrain, further accelerating the decline of traditional industries like pearling.

Though the pearling industry in Bahrain has long since diminished, its legacy continues to influence the country today. The story of Bahrain’s pearling past is preserved through cultural landmarks, museums and UNESCO World Heritage sites. The Pearling Trail, recognised by UNESCO in 2012, offers visitors a glimpse into the island’s pearling history, with sites ranging from traditional diving centres to merchant houses and ancient oyster beds.

Pearling remains an integral part of Bahrain’s cultural identity, celebrated in festivals, art and folklore. The pearl continues to symbolise Bahrain’s heritage, representing the island’s connection to the sea and its history of resilience, trade and craftsmanship. Today, while oil has replaced pearls as Bahrain’s main source of wealth, the memory of the pearling era lives on, reminding the world of the island’s rich maritime tradition.

Tags #jewellery arabia 2024 #BTM NOVEMBER 2024 #pearls in bahrain #bahrain pearl #jewelleryInteresting Fact: By law, in the Kingdom of Bahrain, you can only sell natural pearls. The importing of cultured pearls is not permitted.